Terraform

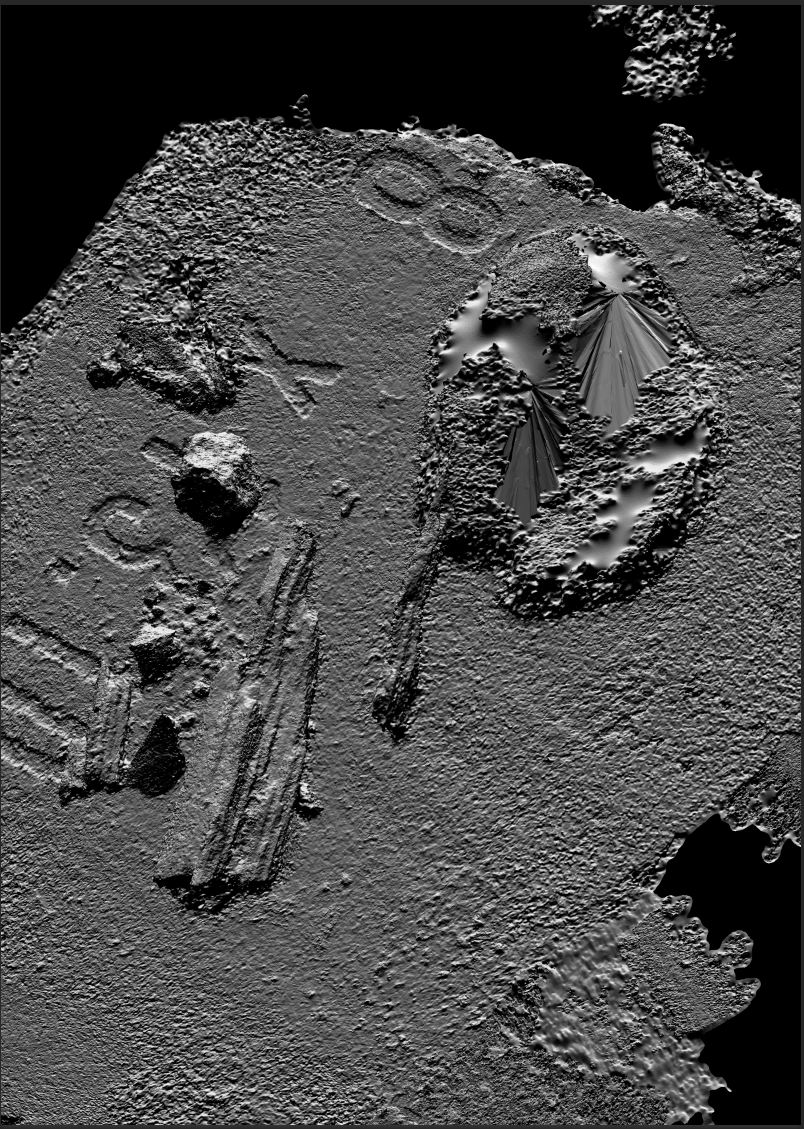

Science fiction landscape paintings at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York. 2018-2019

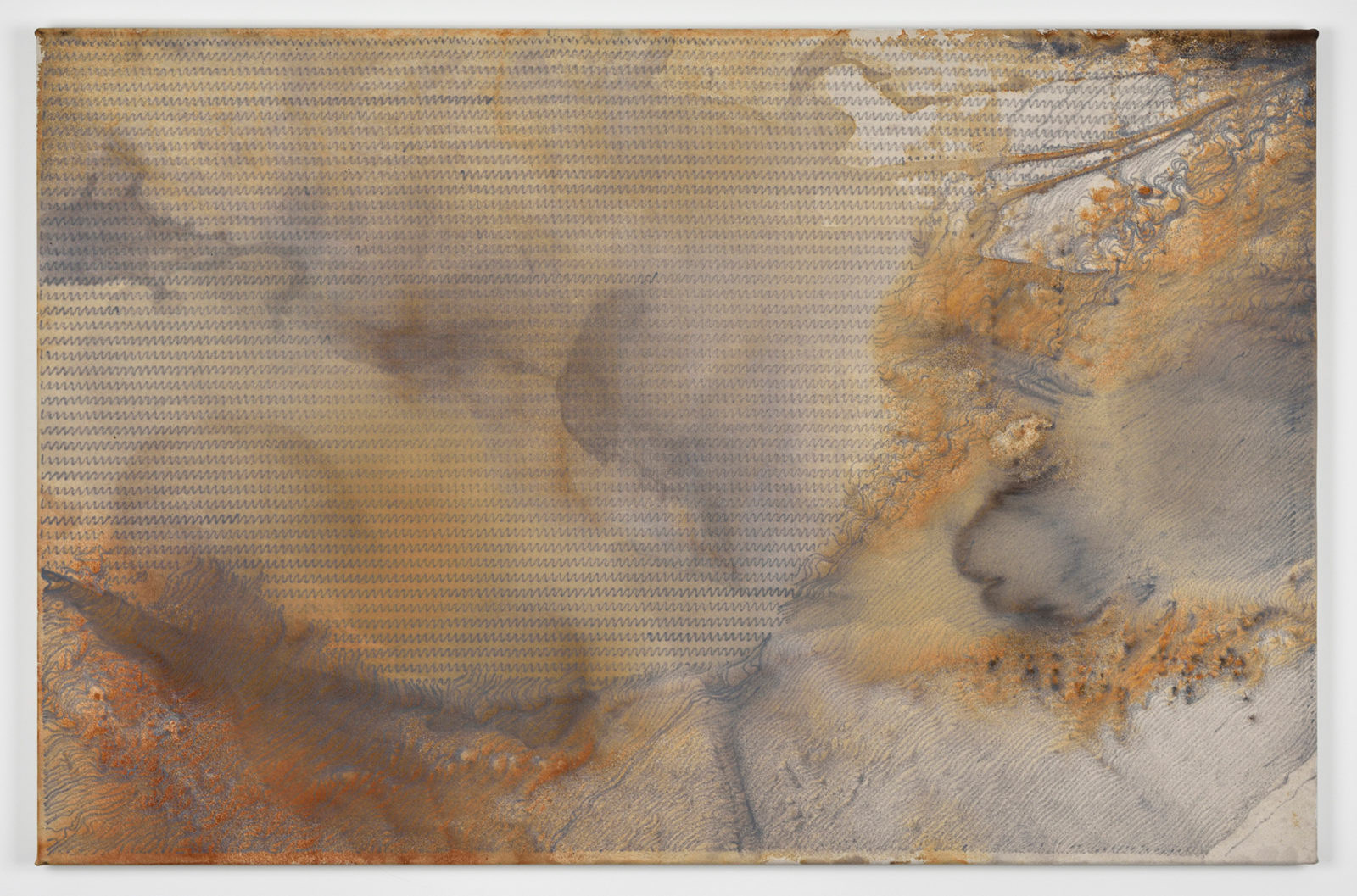

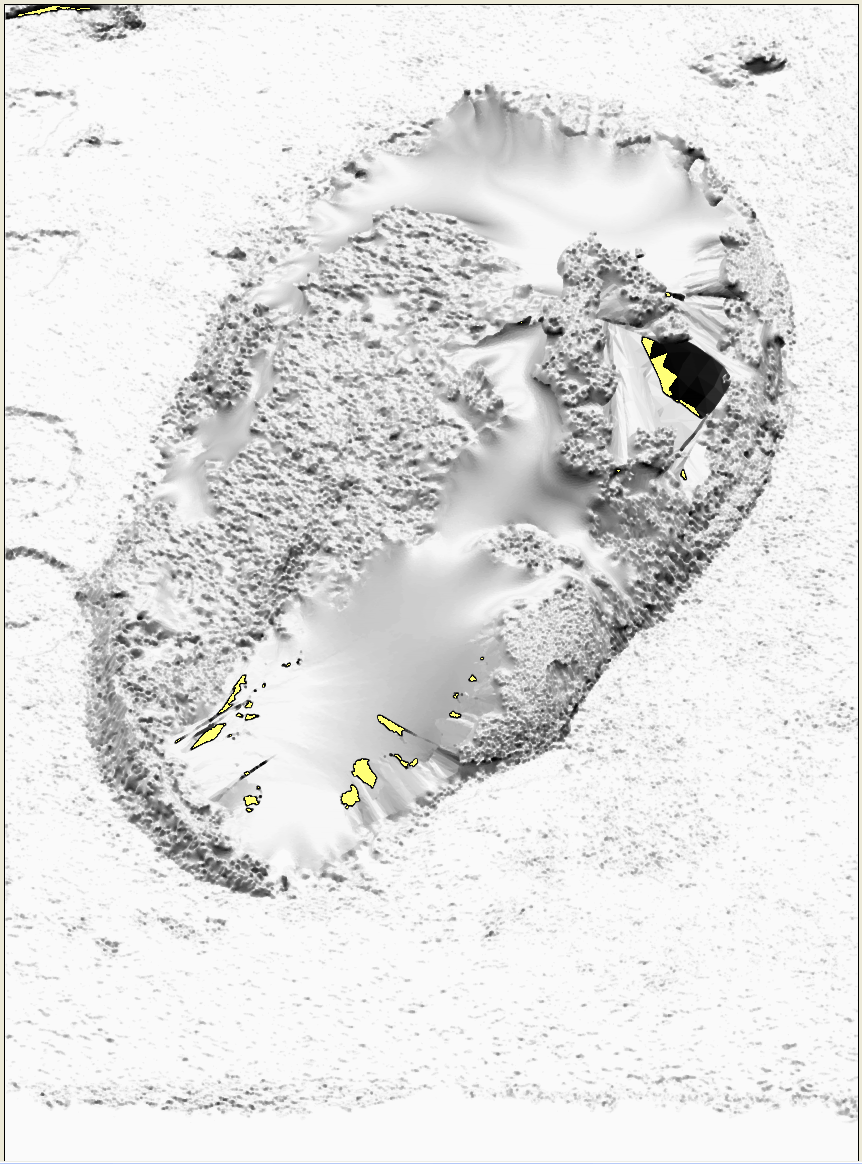

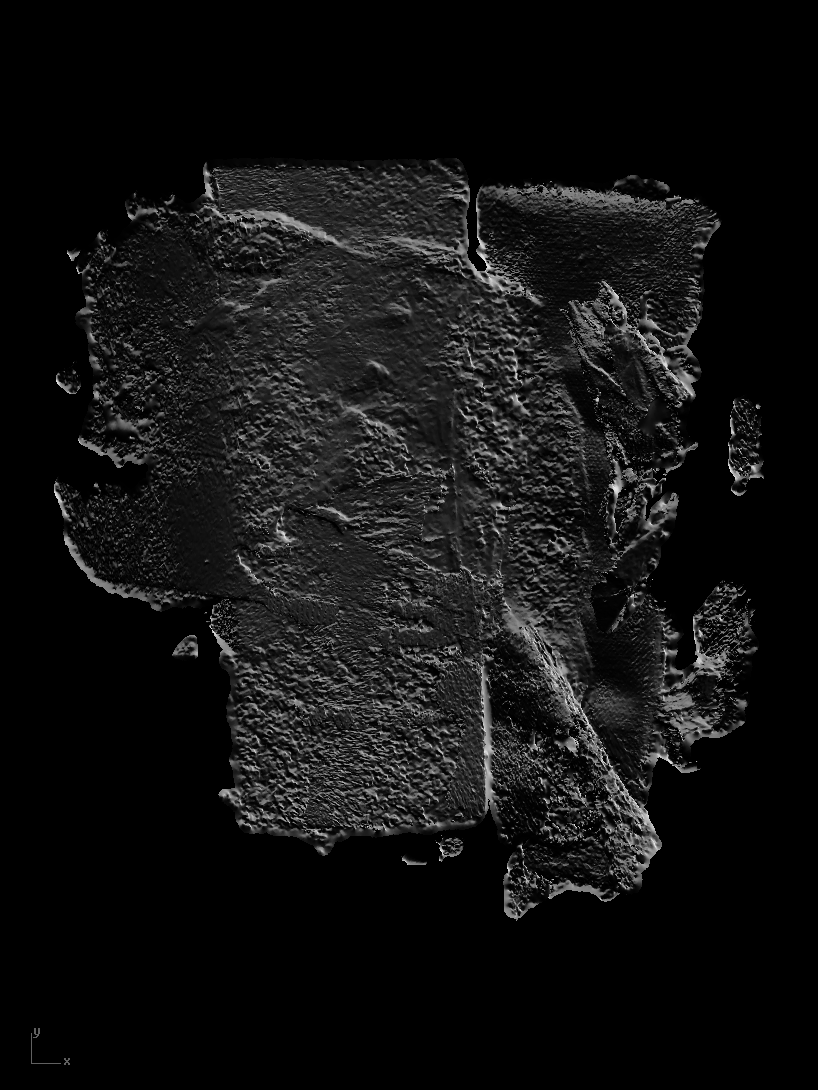

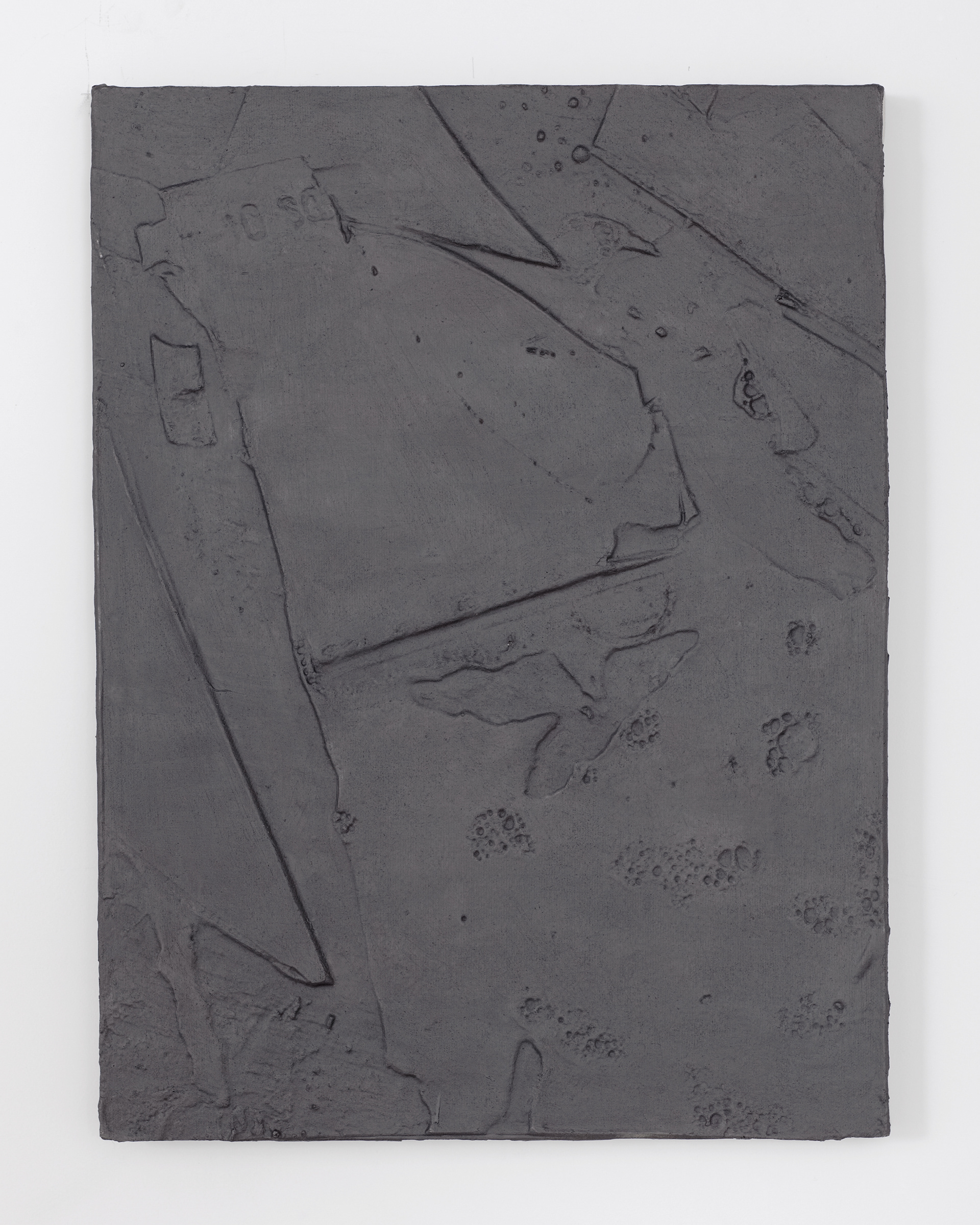

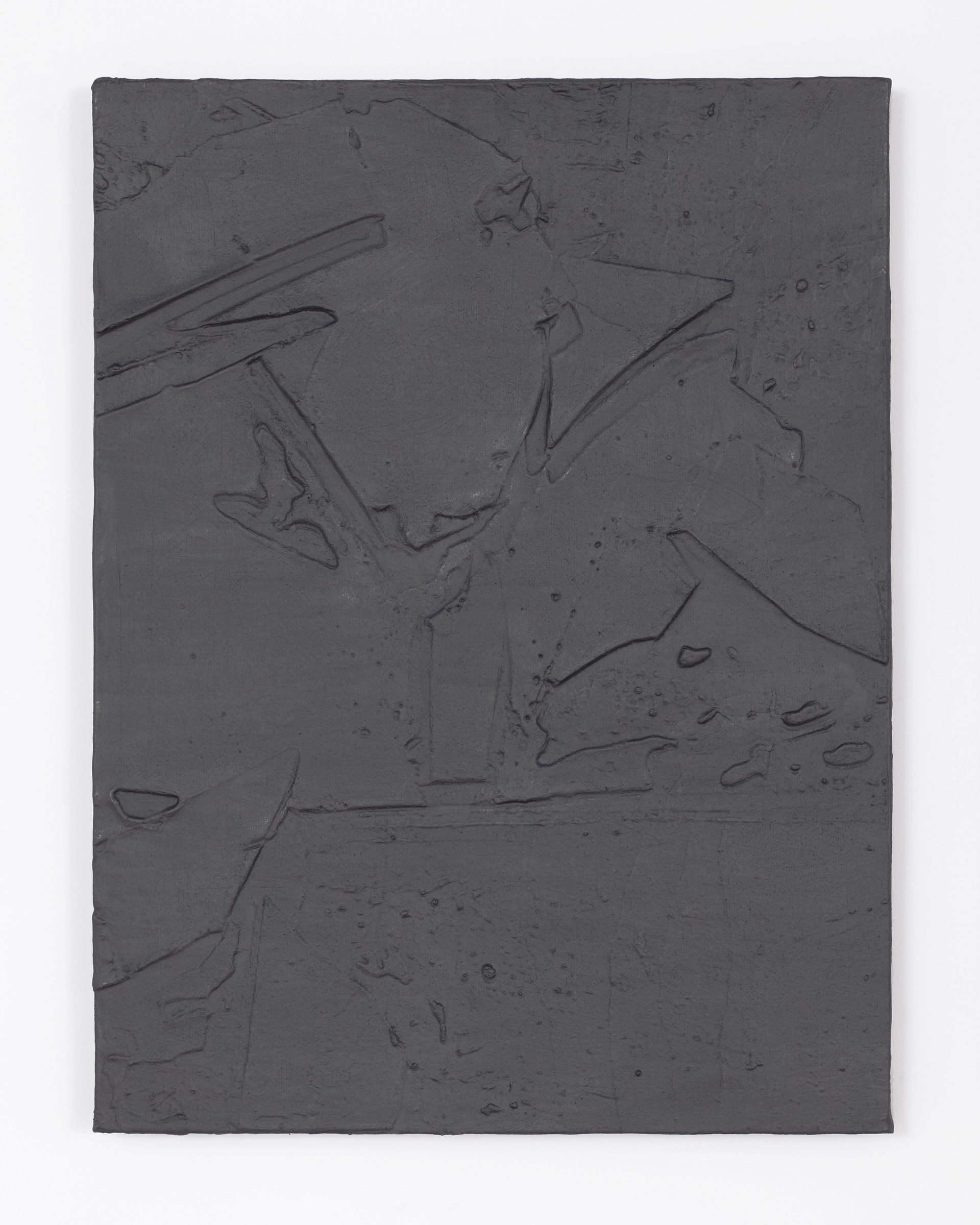

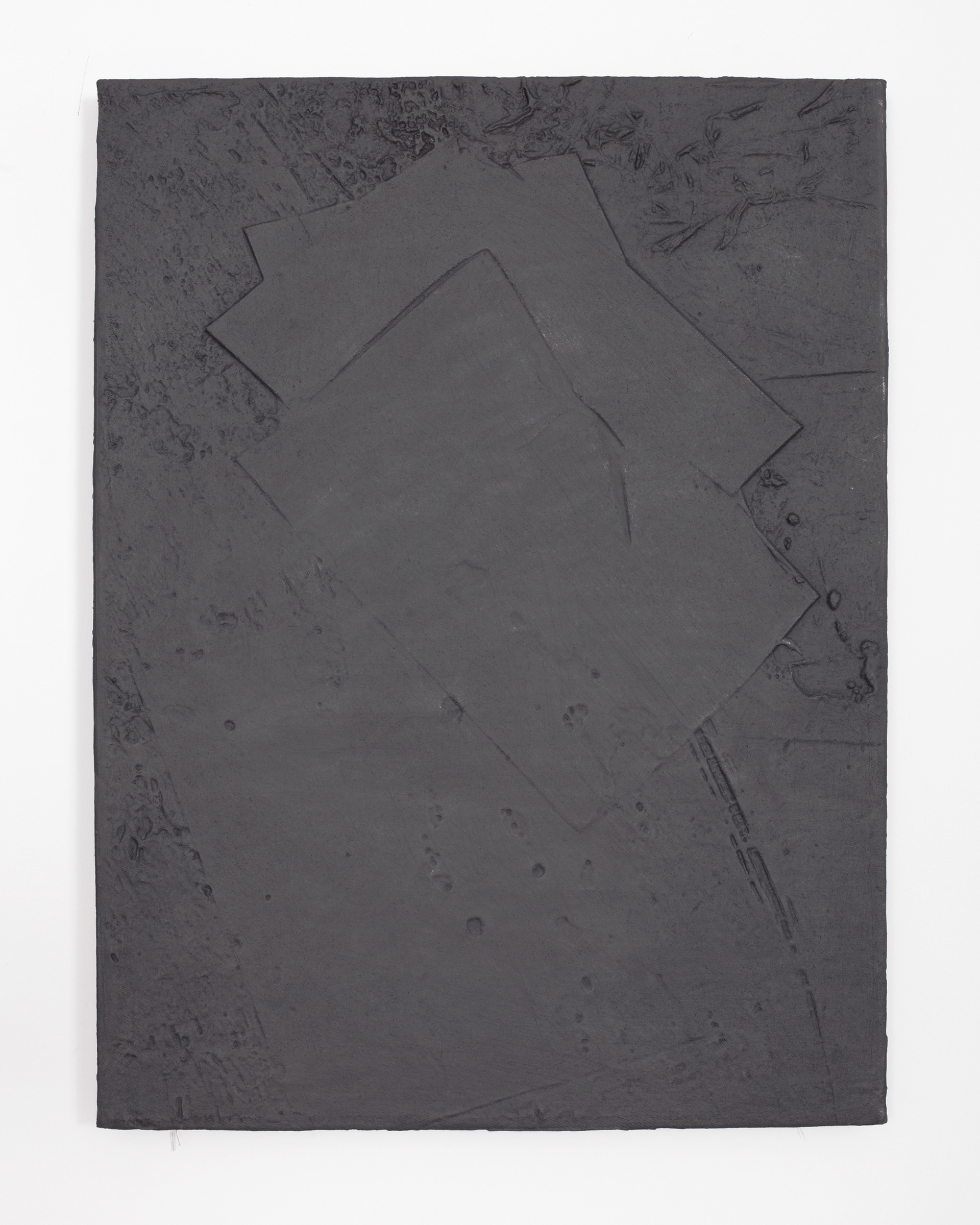

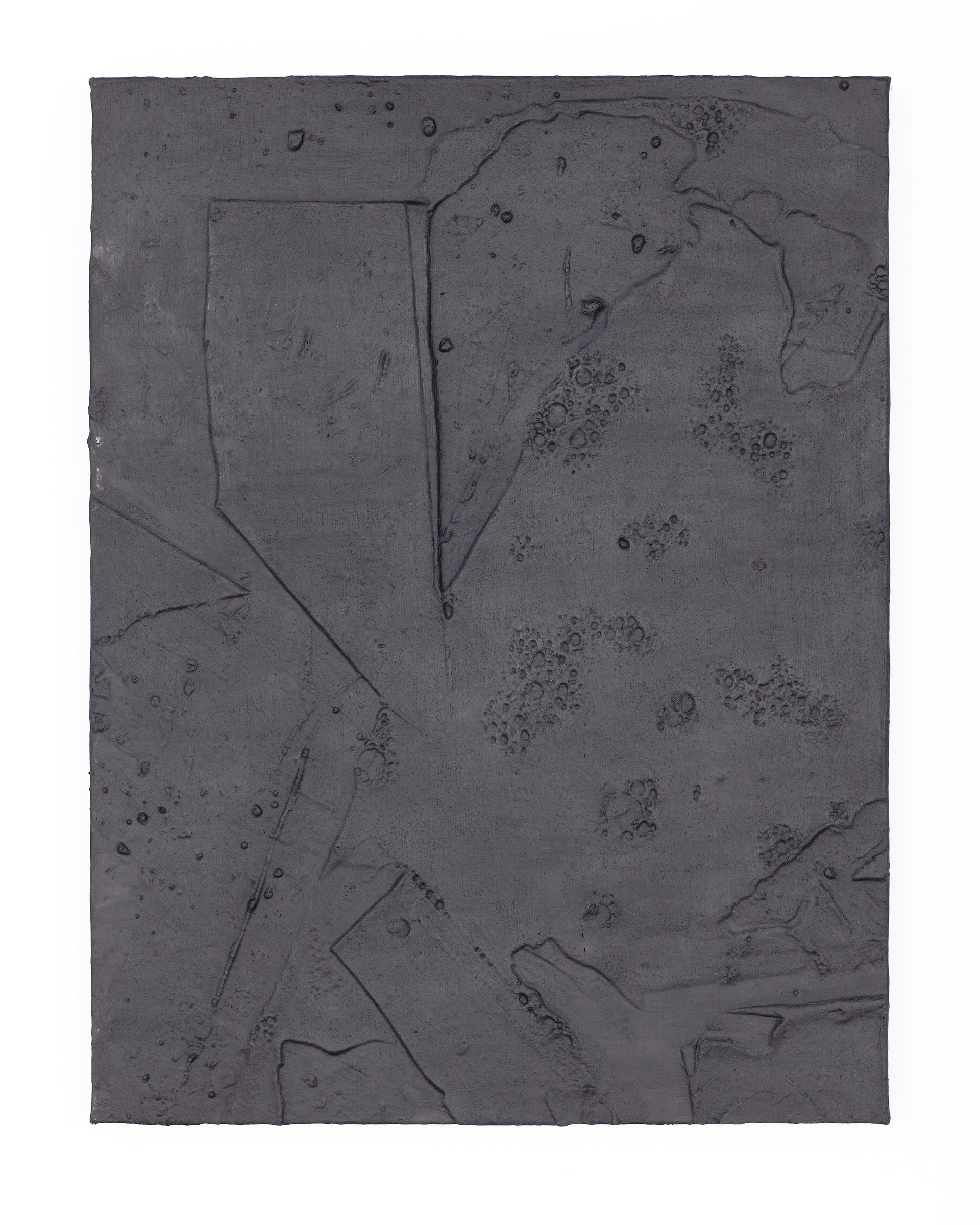

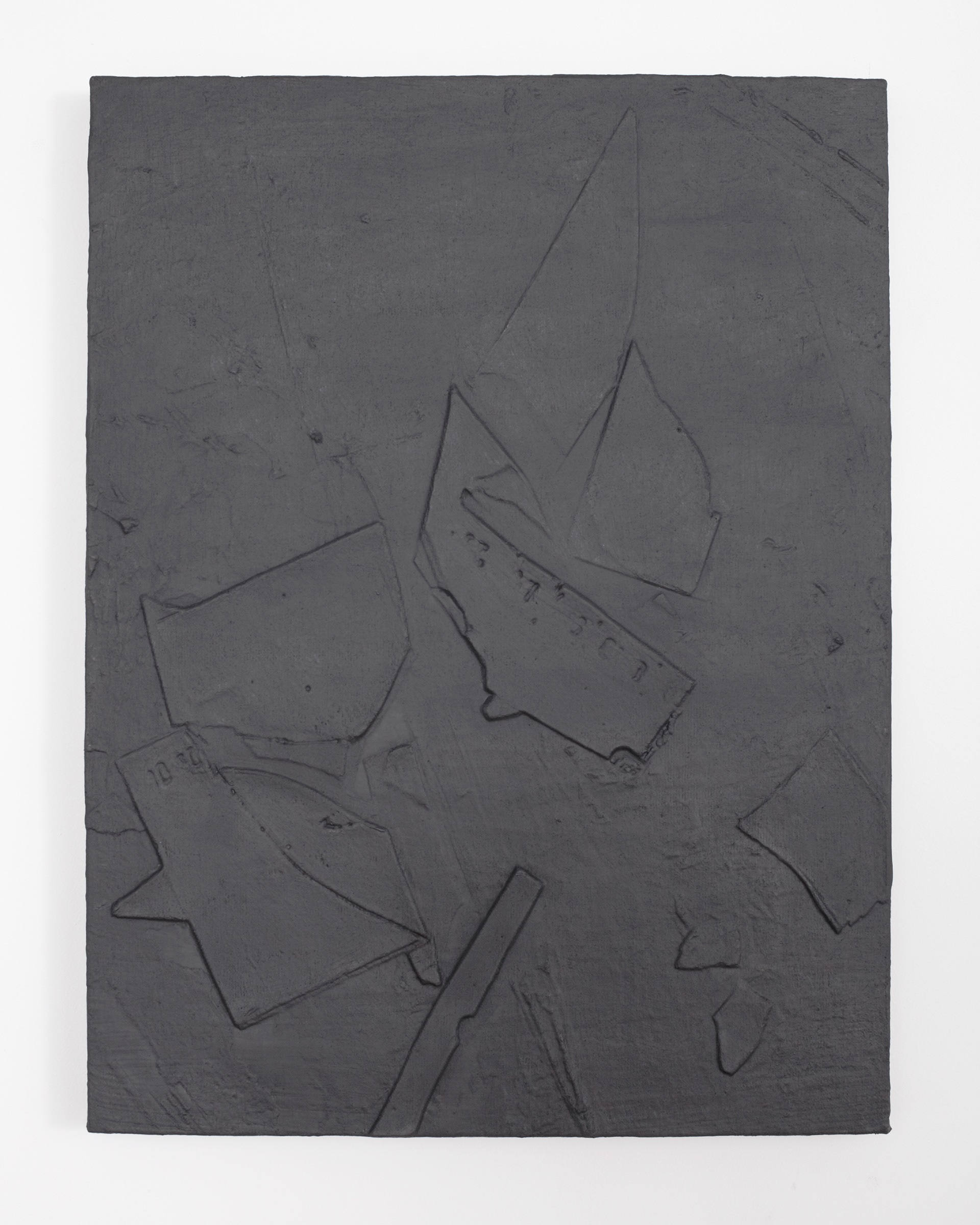

Terraform (Hematite Displacement), 2018, Pigment and acrylic polymer resin on canvas, 28 by 43 in

Terraform (Hematite Displacement), 2018, Pigment and acrylic polymer resin on canvas, 28 by 43 in︎︎︎ DOWNLOAD PDF FLYER with Essay by Claire Lehmann

Press Release

Mitchell-Innes

& Nash is pleased to present an exhibition of new paintings by

Daniel Lefcourt at the gallery’s Chelsea location at 534 West 26th

Street. Titled Terraform, this will be the artist’s second solo

exhibition with the gallery and will feature a set of eight large-scale

paintings.

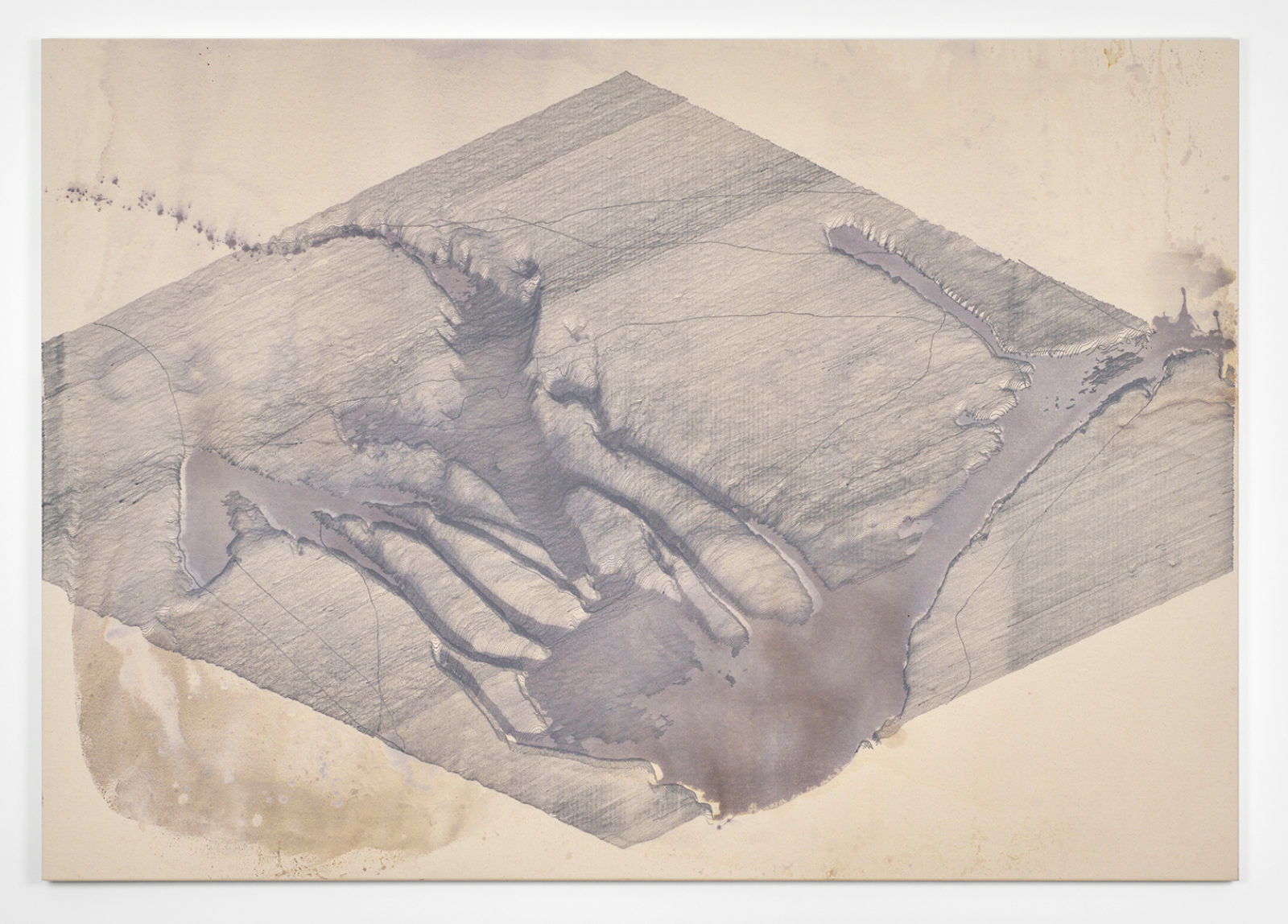

Throughout his career,

Lefcourt has engaged painting through the lens of scientific,

industrial and military imaging technologies. For his latest work, he

has created a set of paintings each depicting an abstract landscape seen

from an aerial perspective. The landscapes do not describe real places,

but are generated by staining the canvas and then tracing the stains

using algorithmically plotted lines. Sometimes the line drawings are

map-like or diagrammatic; in other instances, landforms are described

using hatching and linear perspective. The paintings speak to a history

of art derived from computation and indeterminacy. A history that

includes the generative systems of the artist Hanne Darboven and the

parametric musical scores of Iannis Xenakis.

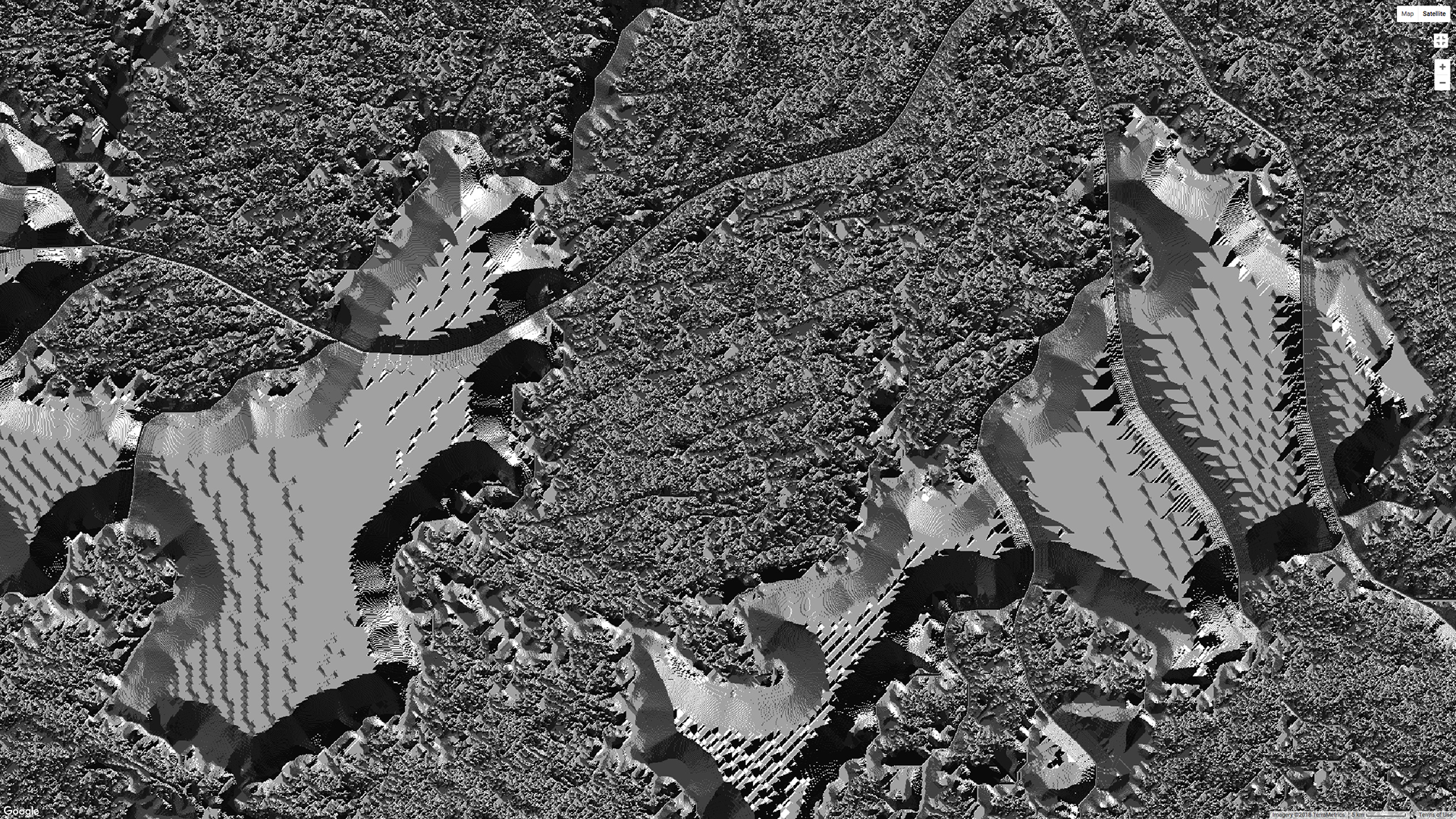

The

aerial view is of interest to Lefcourt because it is a particularly

modern and technological vantage. It is also a gendered perspective. It

correlates with masculine fantasies of dominance, as well as

metaphysical and technological omnipotence. The bird’s-eye view in the

paintings bring to mind drone footage from America’s global military

operations, satellite data of melting glaciers, and the camera movement

in contemporary video games.

Borrowing

a popular term from science fiction, the title of the exhibition,

Terraform, alludes to the influence of authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin

and Kim Stanley Robinson. The authors’ respective works broach the

economic and environmental consequences of our current socio-political

landscape by constructing elaborate fictional worlds. Likewise,

Lefcourt’s paintings offer a vehicle by which we might think on a

geological scale, reflect on our current condition, and imagine other

possible futures

Strata

Science fiction landscape paintings at Campoli Presti, Paris, 2019

Campoli

Presti is pleased to announce Strata. The exhibition will feature a

series of new paintings conveying the impression of abstract landscapes

seen from an aerial perspective. The works continue the artist’s

exploration of painting in relation to technical and scientific imaging.

An important reference for Lefcourt’s landscapes was the recording of the first image of Mars by Nasa scientists in 1965. The initial planetary image was taken by a satellite and transmitted to Earth as a numerical sequence representing varying tonal intensities. Lower numbers represented darker, or lower areas of the terrain, while higher numbers represented elevated plains or mountains.Due to time constraints to obtain a detailed photograph, the values were initially decoded by the scientists using oil pastels. Thus, the first representation of Mars was a hand-painted sketch. The image’s truth claim inscribes itself into the history of aerial photography - patented by French portraitist Nadar in 1855, the technological development of aerial views has escalated with the use of satellite imagery, paired with military domination.

For Lefcourt, the Nasa painting of Mars is a vivid example of a mediated painting process. On the one hand, there is the arbitrary surface of the terrain produced by chance geological events, while on the other hand there is a rigid, numerical encoding of this natural surface into a grid of values. This relationship between chance and encoding provided Lefcourt a structure from which he could develop his work. Viewed from a distance, Lefcourt’s topographic lines and terrestrial surfaces hold out the possibility that the images represent specific locations on the earth or elsewhere. Only upon reflection does one realize the map-like drawings are actually responding to the stains and drips of the painted surface below. The work begins by using chance procedures to apply washes of pigment to an untreated canvas. The canvas is then photographed, and the image imported into 3-D software. At this stage Lefcourt begins to program lines, marks, and diagrams analyzing the surface of the canvas as though it were a dimensional model of a landscape. The resulting points and vectors are later rendered on top of the original stained canvas using a computer-controlled plotter that Lefcourt constructed for the series. Approached as a test field, Lefcourt’s canvases articulate the distance between the aleatory application of paint and the regulated mapping of those same actions in a single terrain – the terrain of the painting.

Lefcourt’s work reflects on contemporary image production while negotiating the reality of material procedures within the historical genre of Landscape Painting. In her essay dedicated to this body of work, Claire Lehman sees the lines and marks laid down mechanically as “remnants of optical effects - from the camera lens that provides the digital visual data to be extrapolated from a previously uncharted surface, that of Lefcourt’s canvas.” She continues, “Isn’t every canvas, at the beginning, a world unto itself, an environment in which chance and intention can combine to produce an image of intelligence, allegory, even fantasy?”

1. Lehman, Claire. Terraform, November 2018, p. 3.

Cast

at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, 2015

March 7–April 18, 2015

At a data visualization conference a few years ago, a colleague passed me a piece of paper with an Internet address written in nearly illegible handwriting. The address didn’t start with “http://www”; instead it was a protocol I had never used. I showed it to a tech savvy friend, who suggested I only visit the link anonymously. Curious, but not knowing what I would find, I decided I better not use my home network. I went to one of the remaining public libraries in the city and opened the TOR network on my tablet.

At a data visualization conference a few years ago, a colleague passed me a piece of paper with an Internet address written in nearly illegible handwriting. The address didn’t start with “http://www”; instead it was a protocol I had never used. I showed it to a tech savvy friend, who suggested I only visit the link anonymously. Curious, but not knowing what I would find, I decided I better not use my home network. I went to one of the remaining public libraries in the city and opened the TOR network on my tablet.

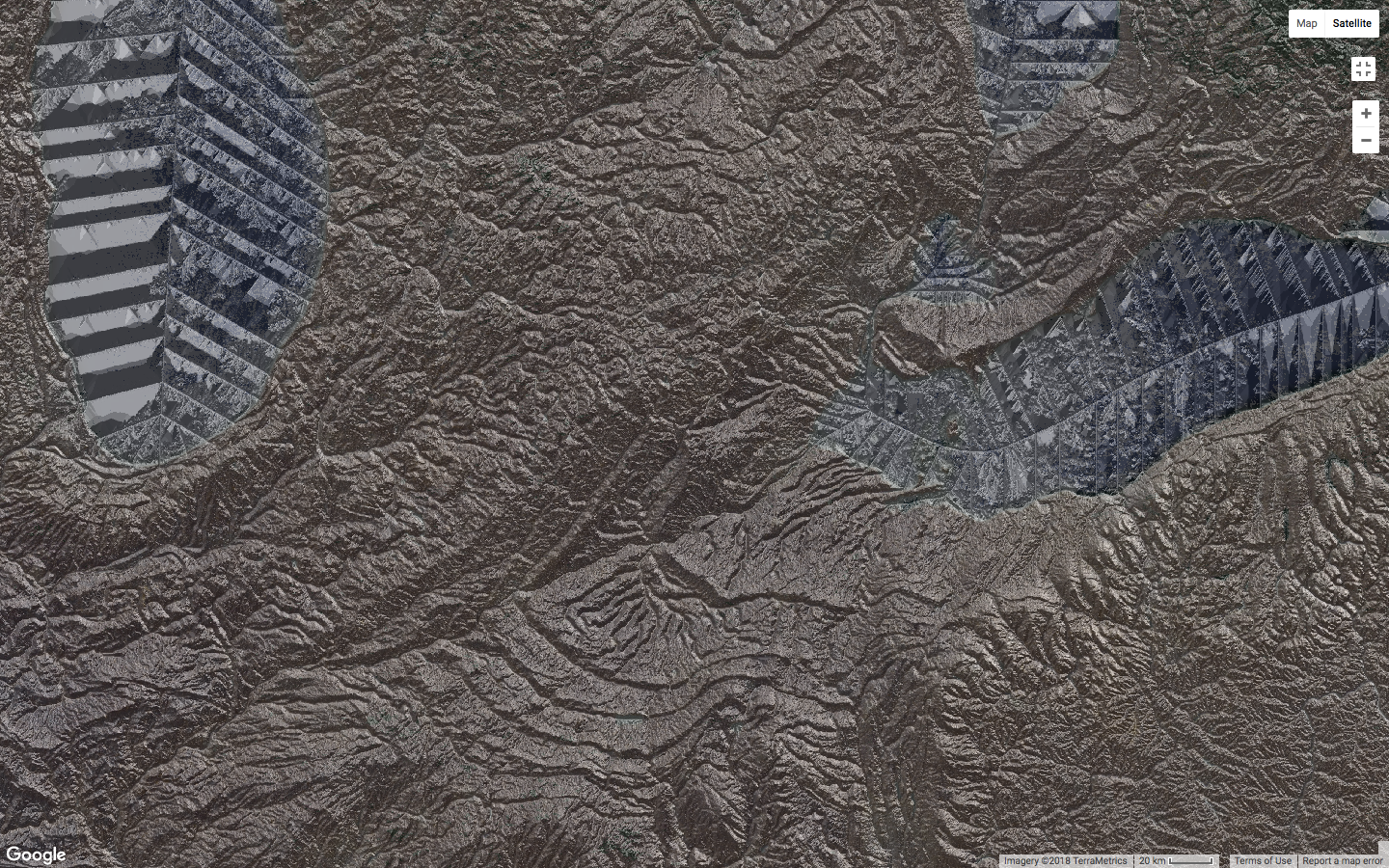

What I found

was a database of JPEG, AVI, PDF, DXF and GIS files, along with an

antique Google maps-like application that allowed one to zoom in and out

of high-resolution satellite images of various locations using pinching

gestures. I ran my fingers over the terrain, which was labeled in a

code unknown to me. A quick search revealed there were hundreds of

thousands of items in the database.

The

first file I opened was a PDF document on the history of

photogrammetry – a technique in which photographs are used to measure

scale and distance. Another query brought up a PowerPoint presentation

on model making and subtractive manufacturing. There were documents and

examples of the relationship between pantographs and “point

clouds.” There were also thousands of files that contained soil sample

data and information from a materials library.

The

most memorable files were video stills that appeared to have been

captured directly from satellites or unmanned aircraft. They were what

filmmaker Harun Farocki has called Operative Images – images that exist

merely to gather data. Some of the content was deeply upsetting, though

it was unclear to me at the time if the stills were simulations or not.

These files were the exception though – the majority of the content had

to do with techniques for input, processing, and output.

On

my next visit to the library, the database was empty. The interface was

there, but the content failed to load. The screen stopped responding to

my touch. As I closed the browser, and wandered through the library

stacks, I realized that I had stumbled upon something

significant – perhaps, this could be a useful methodology…. The database

was an allegory…. Maybe I have to enact a similar set of operations….

-- Daniel Lefcourt

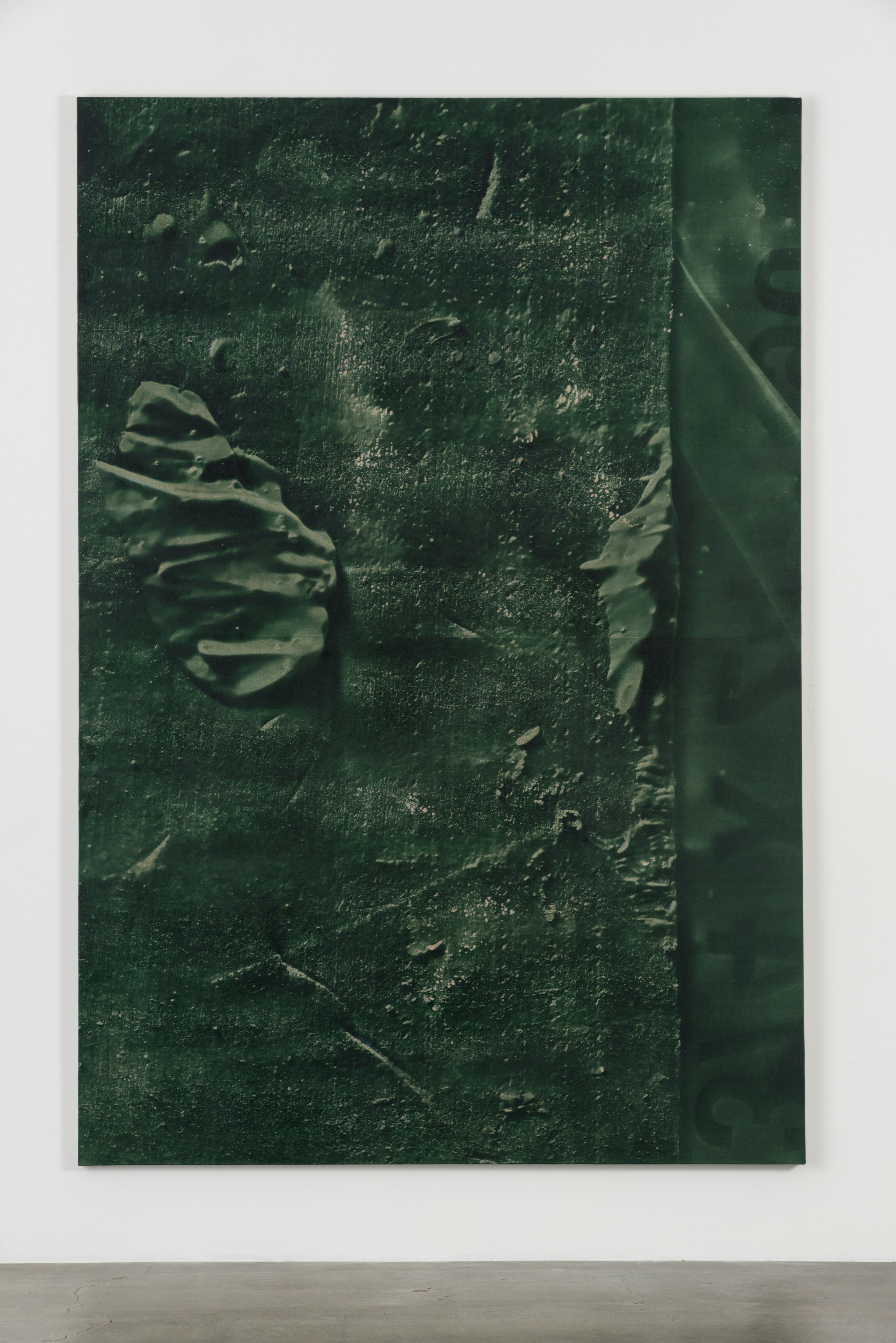

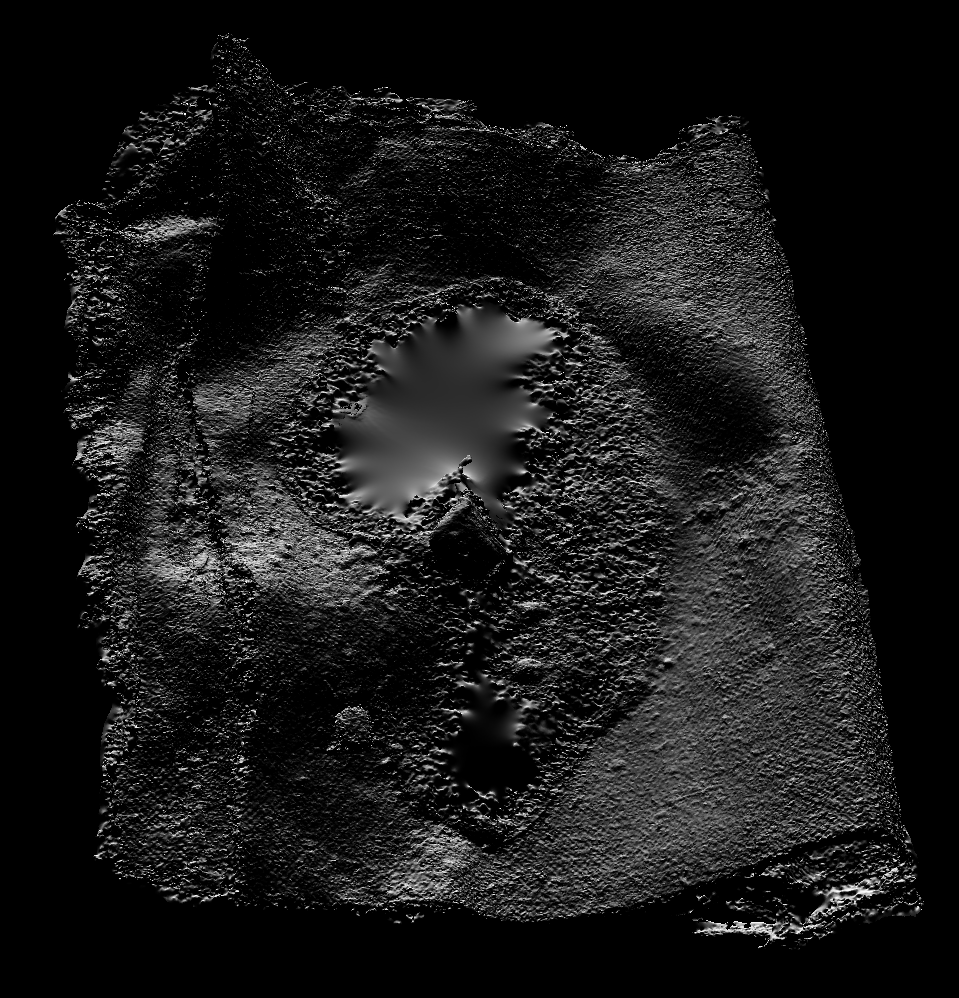

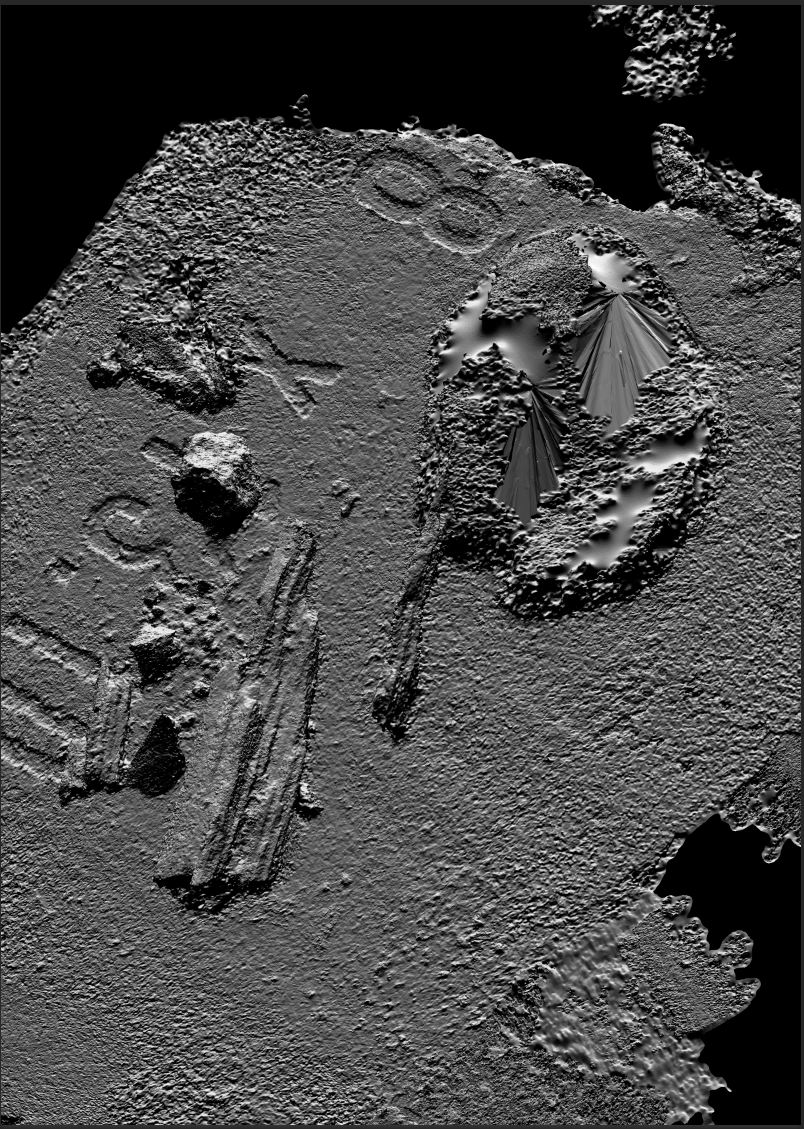

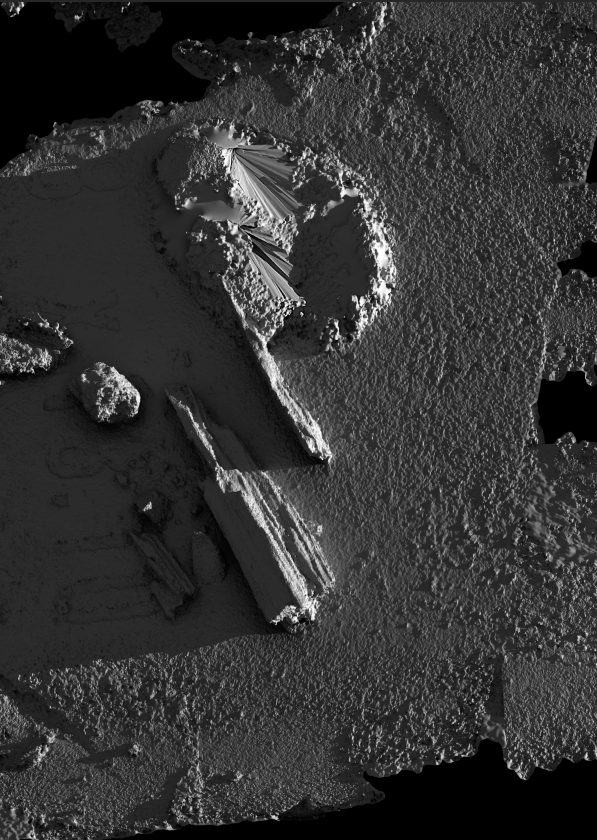

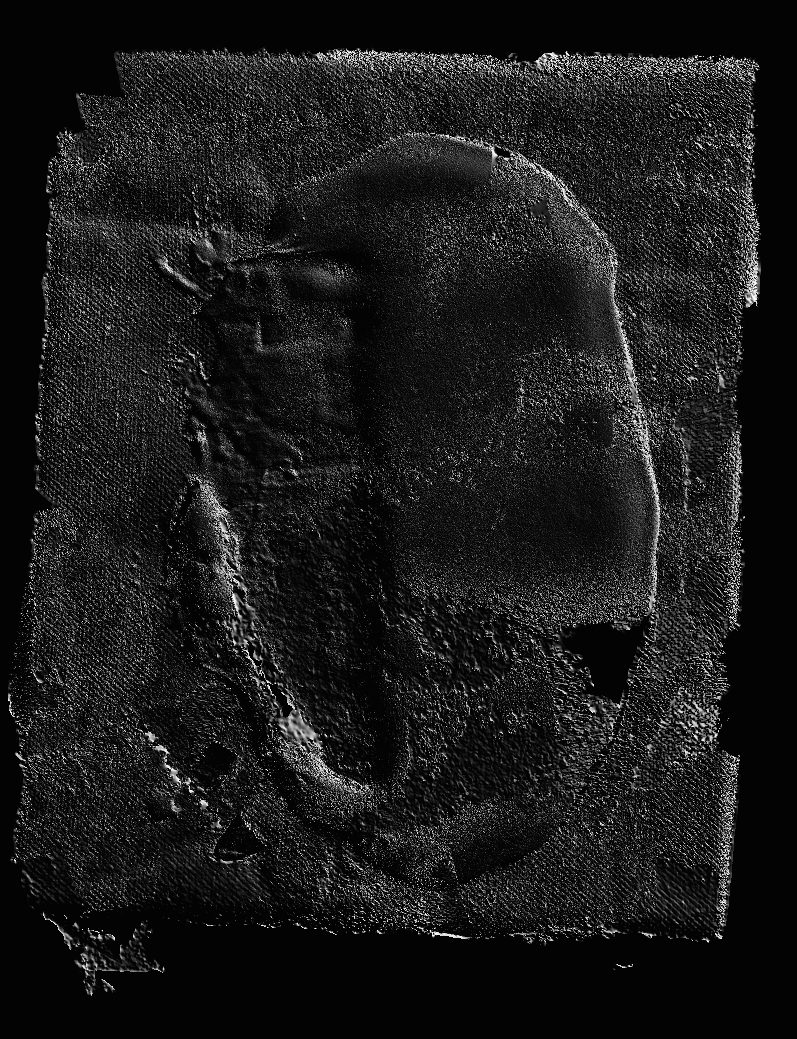

Blum

& Poe is pleased to present Daniel Lefcourt’s first solo exhibition

at the gallery, which includes new large-scale paintings, relief

panels, and a selection of works on paper. All of the works in the show

are derived from small cultivated accidents created in the studio – a

puddle of water and glue spilled on a debris-covered tarp or a spot of

paint dropped arbitrarily on a board. Measuring no more than a few

inches, the scenes are digitally photographed dozens of times from a

number of angles to generate a 3-dimensional computer model, from which a

low-relief foam carving is manufactured. Paint is poured into the

low-relief mold, allowed to dry, peeled off, and adhered to a large

canvas. The final result of Lefcourt’s technique is a set of spectral

images with an intense physical presence.

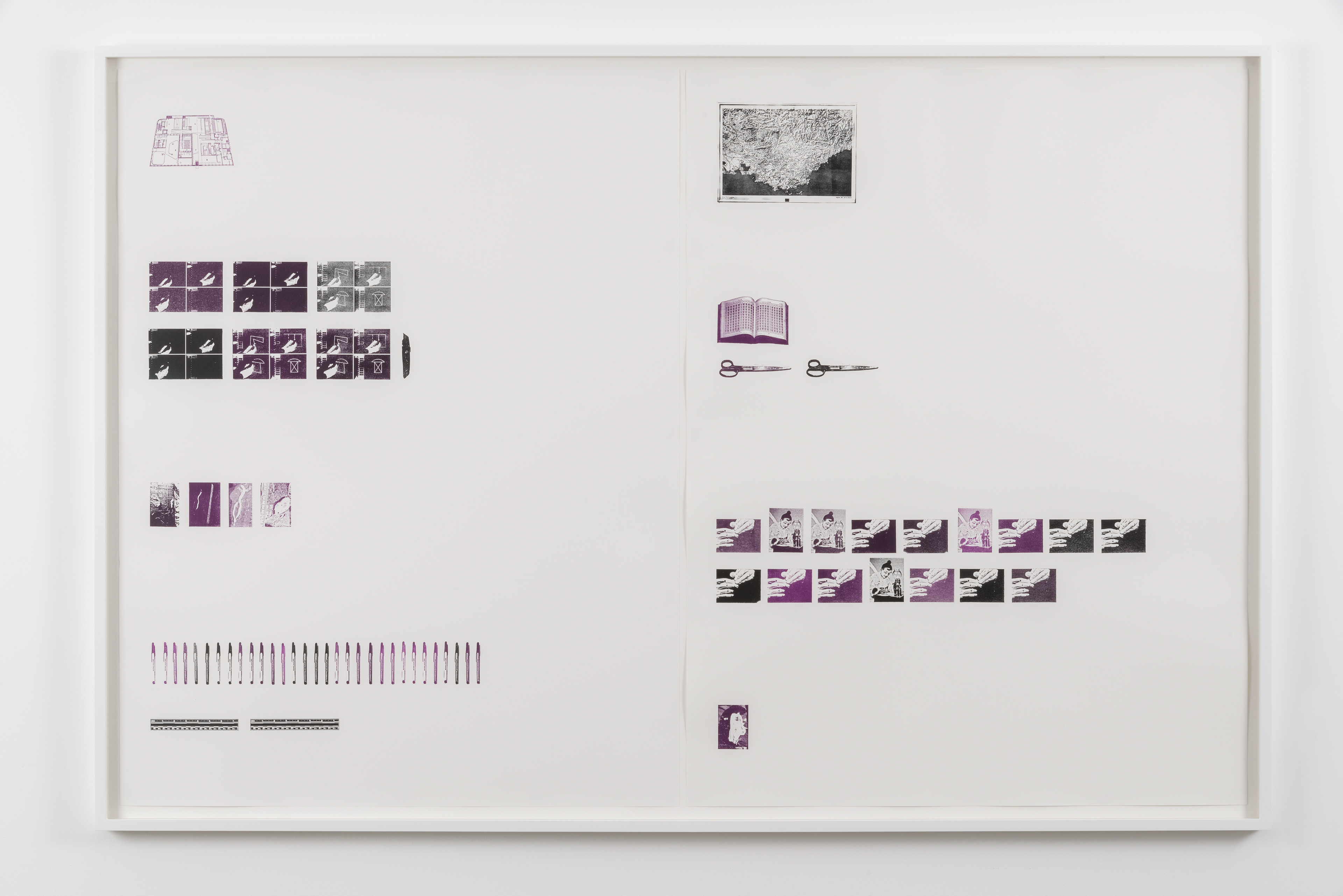

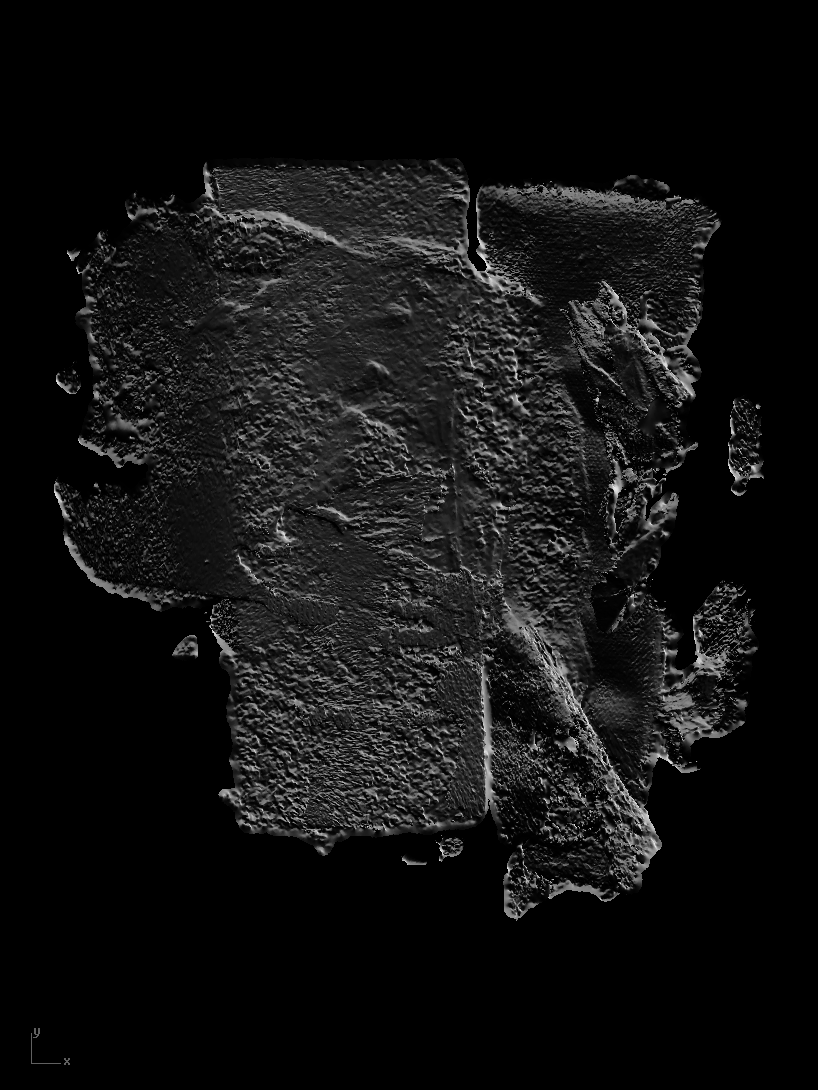

Anti-Scans

Press Release

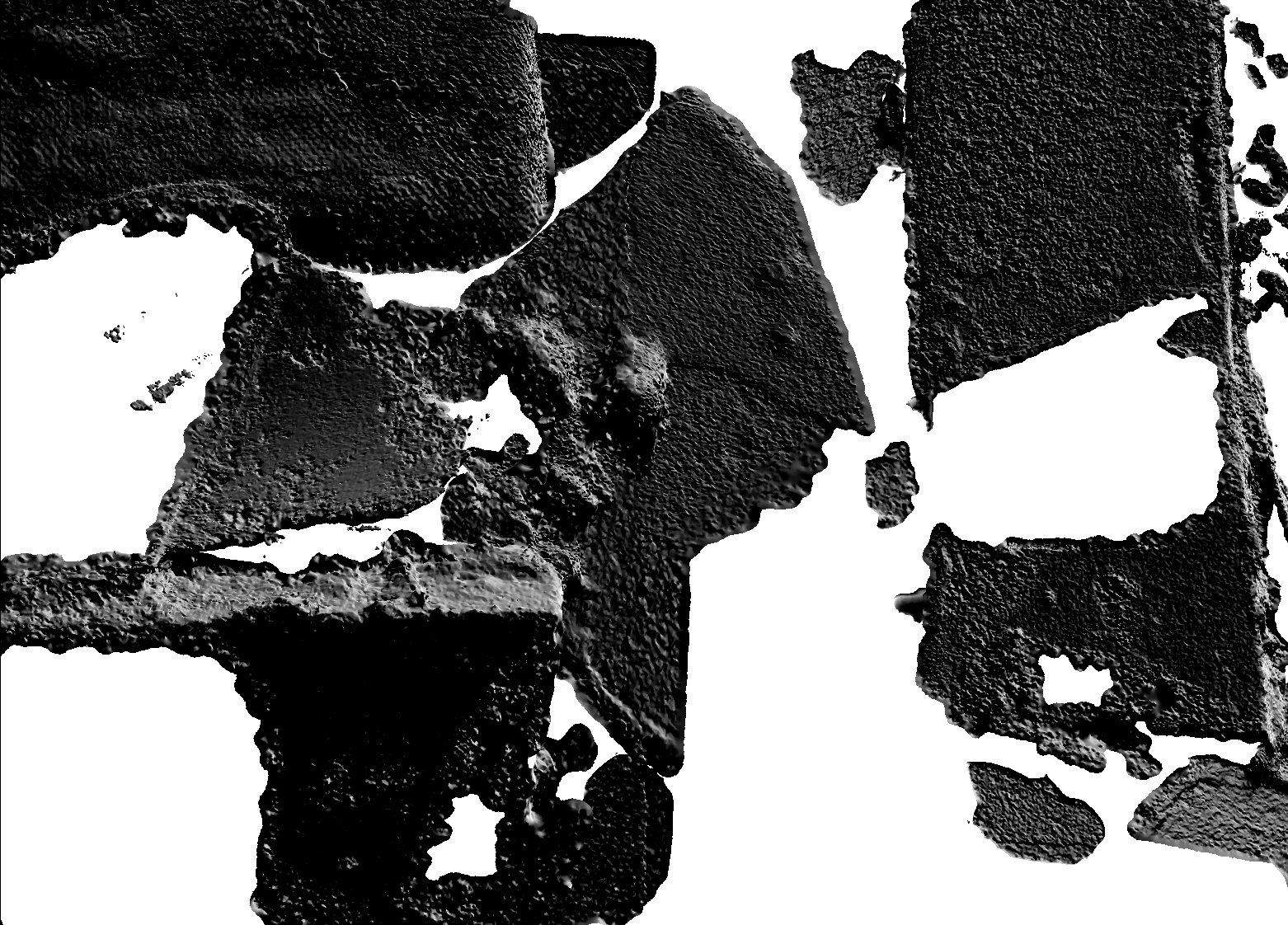

Campoli Presti is pleased to present Anti-Scans, Daniel Lefcourt’s sixth exhibition with the gallery. Throughout his career, Lefcourt has continually engaged the space between painting and technical imaging. By using scientific, commercial, and military technologies to create his work, Lefcourt draws painting into the broader conflicts and politics of representation.

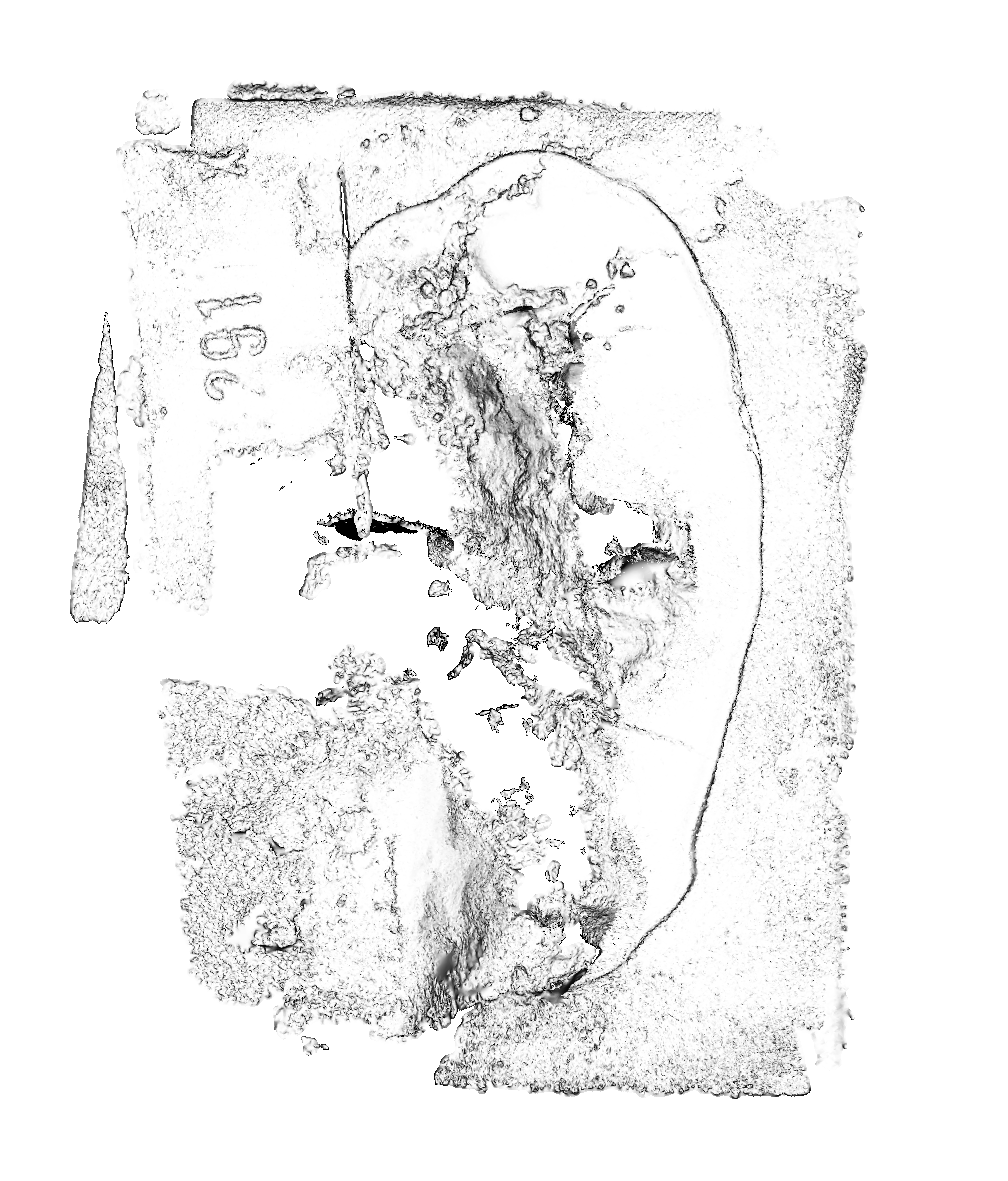

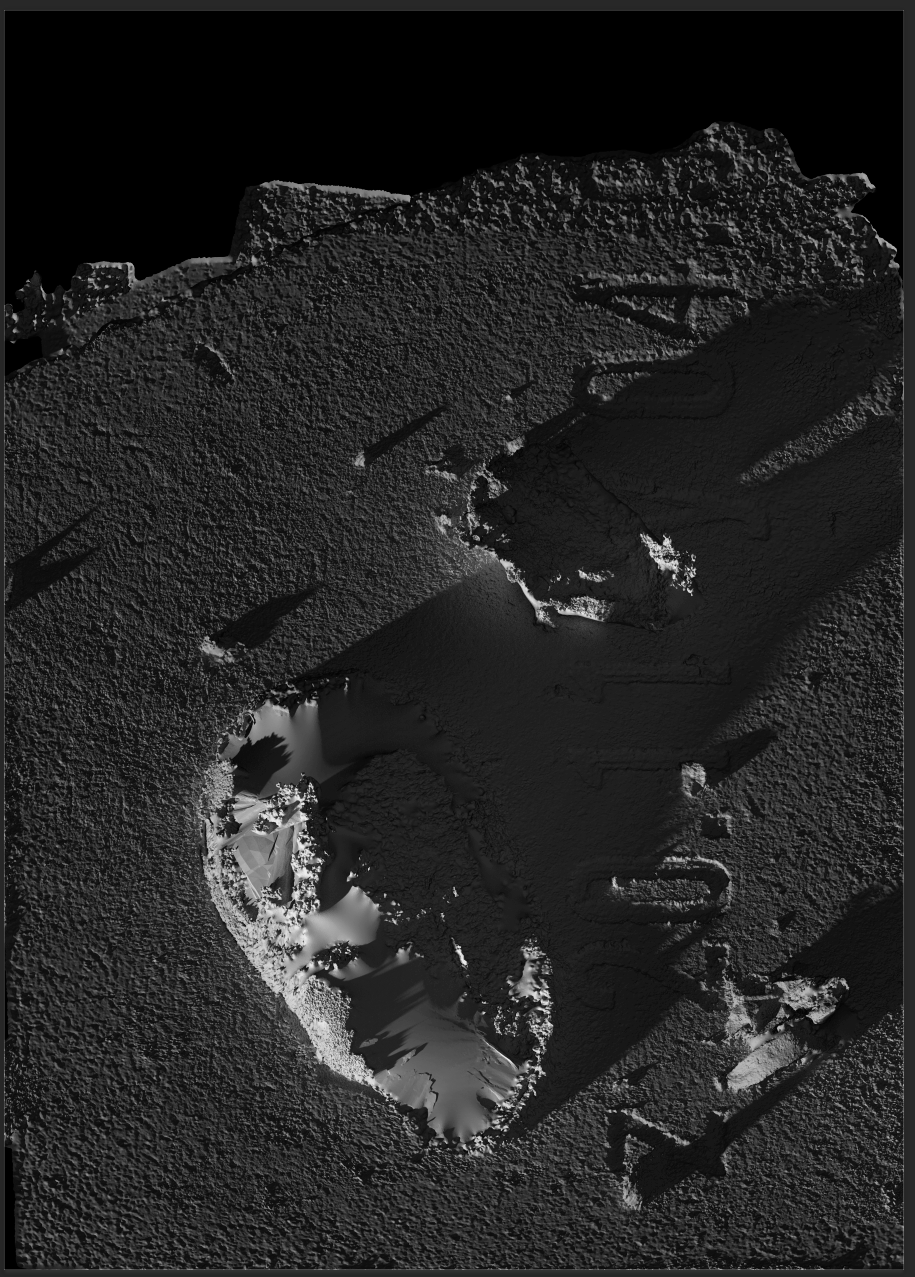

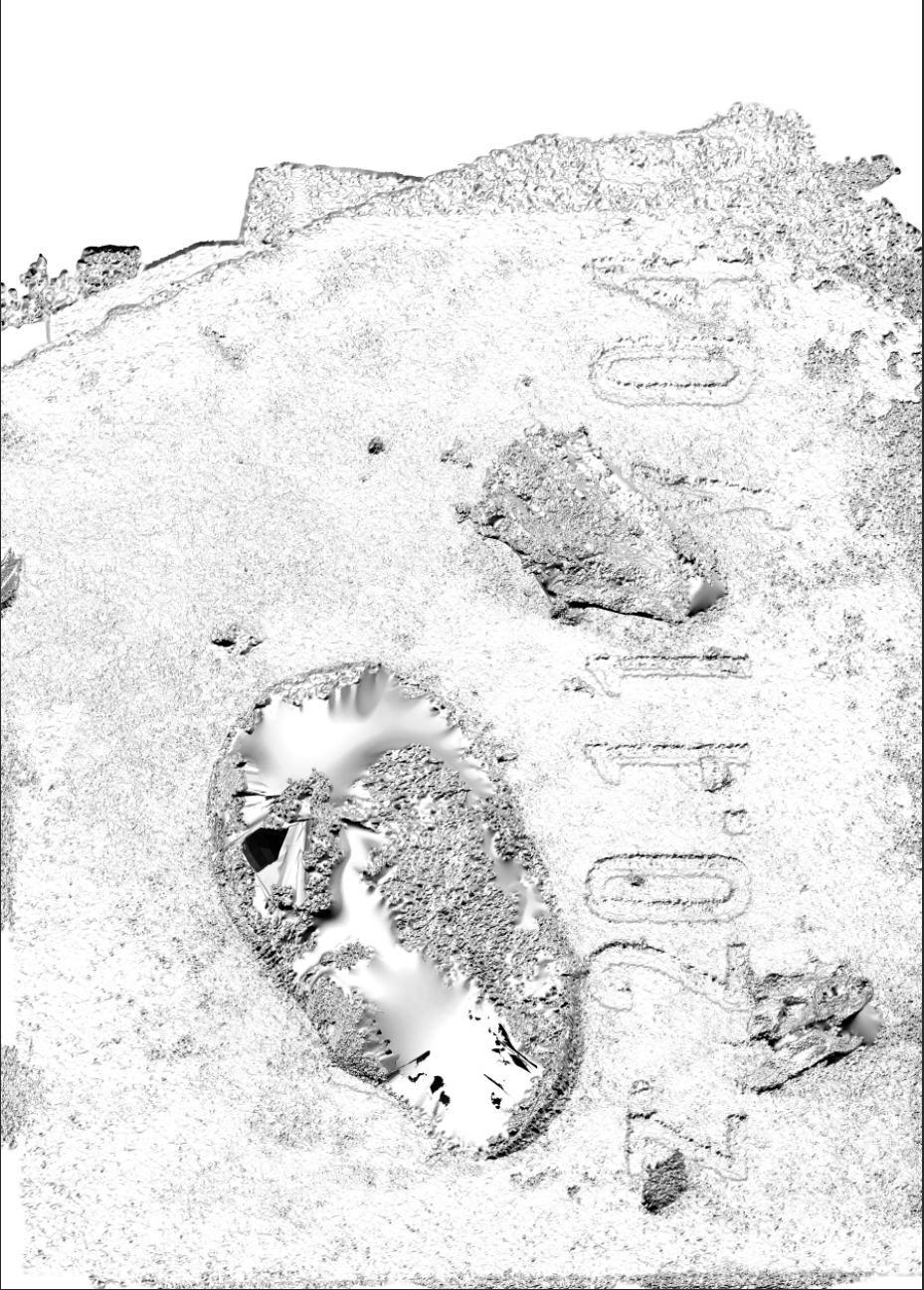

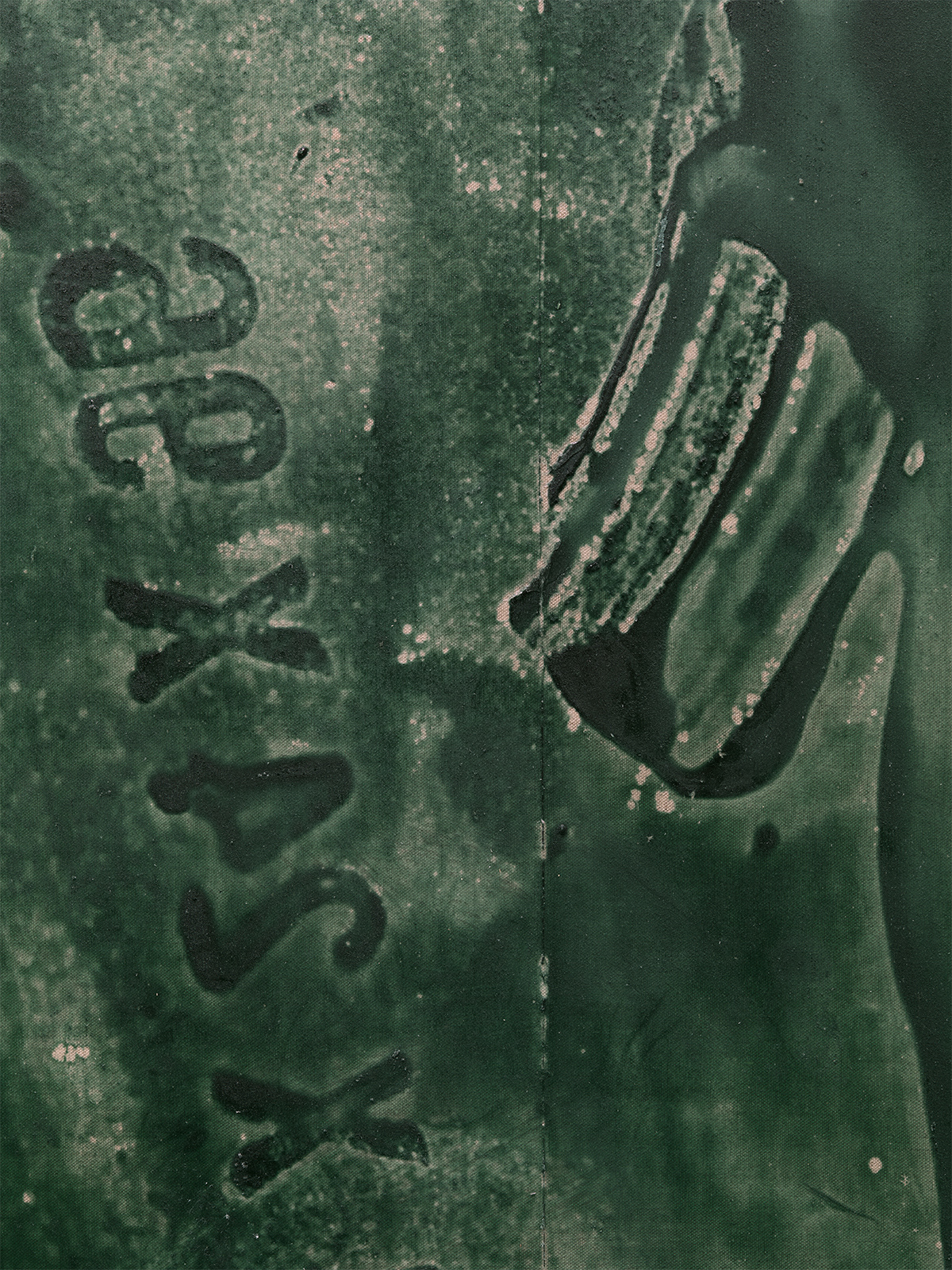

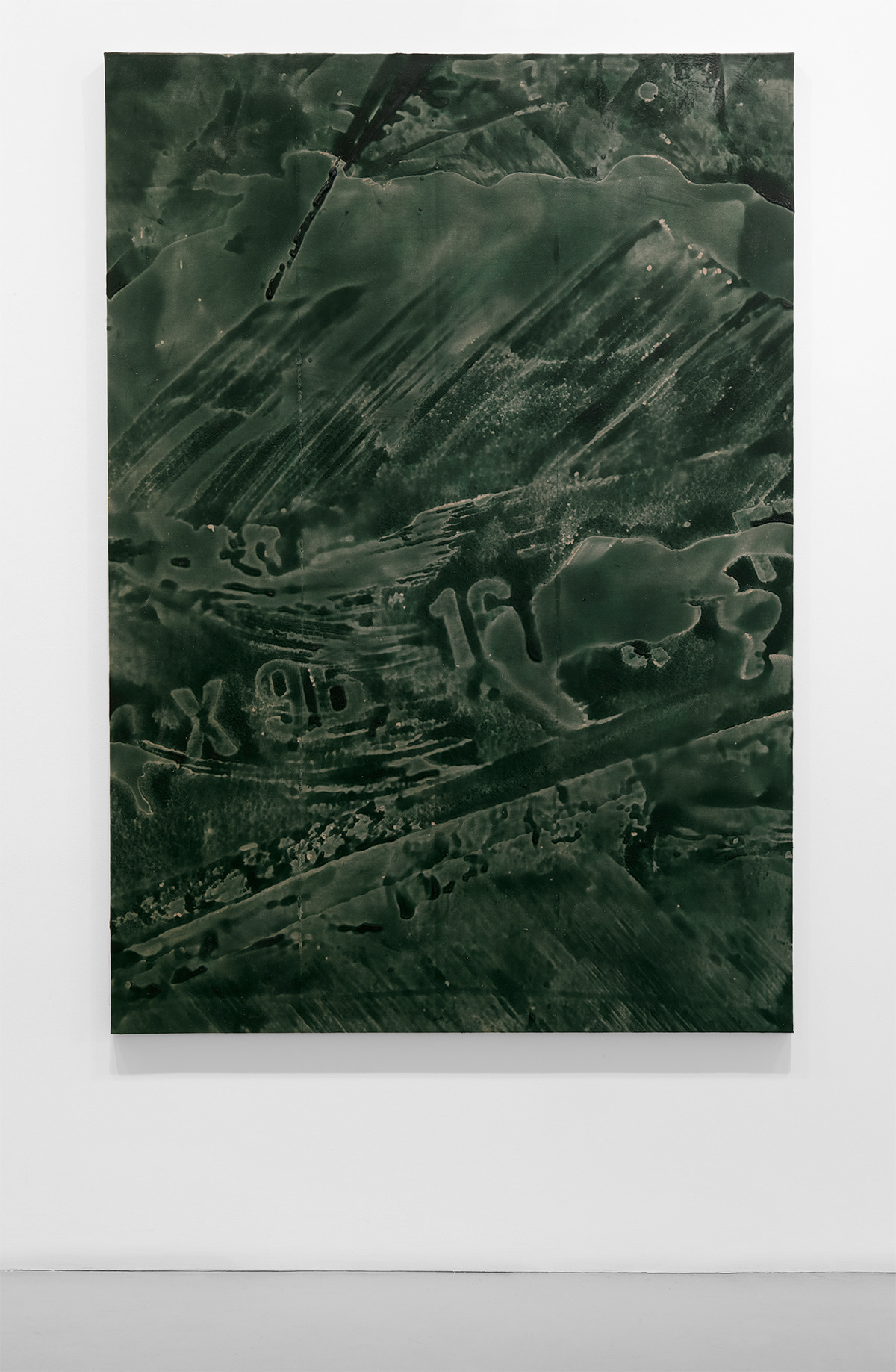

To create his new series of paintings, Lefcourt has used 3-D scanning techniques (photogrammetry, laser) originally developed for the fields of archeology, forensics and cartography. While the scientific fields that use these methods are concerned most of all with accuracy, Lefcourt uses 3D scanning as the basis for a material play with the languages of painting.

The works featured in Anti-Scans present surfaces and supports such as canvas and wood, as well as painting media and pigment. The reflections and movement of the paint while it is still in motion creates unpredictable distortions in the scanned model – what was a smooth reflective surface might translate as a crystalline structure, or simply an empty gap – while the detailed surfaces on which the paint sits, create a legible, if artificial, ground.

Anti-Scans are precise recordings of the material world, but they are also a kind of digital hallucination. The scans are simultaneously highly detailed, yet filled with errors and glitches. These temporary aberrations have been captured, enlarged, and ‘stored’ as paint on canvas. Counter-intuitively, it is the errors in the scans – and the subtle variation in each painting – that serve to register the material basis of digital input and output.

Alongside the paintings are two new pairs of drawings that conflate various historical methods of image production. Over the course of the past year

Lefcourt has created a large set of rubber stamps using a laser engraver – all the imagery relating to the paintings, and to the production of technical images in general. For Lefcourt, this collection of stamps is a kind of historical database – each image stored in rubber hardware. This database can be queried, returning the results by hand-printing each stamp individually, in varying tones and sequences.

Lefcourt has created a large set of rubber stamps using a laser engraver – all the imagery relating to the paintings, and to the production of technical images in general. For Lefcourt, this collection of stamps is a kind of historical database – each image stored in rubber hardware. This database can be queried, returning the results by hand-printing each stamp individually, in varying tones and sequences.

While the works at first appear to be descriptive and ‘readable’, this apparent legibility is continually frustrated and postponed. Instead we are left with a rigorously abstract set of artworks. Ultimately, the Query drawings are a rebus, structured by rhythm and sequence.

Modeler / Cast Paintings 2011-14

Modeler at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, 2013

Press Release

Mitchell-Innes & Nash is pleased to present our first solo exhibition of Daniel Lefcourt. Modeler will include new paintings and graphite panels within a modified exhibition framework.

The exhibition title Modeler evokes someone – or something – making a scale model construction. It is this emphasis on making that captures Lefcourt’s interest: a fixation on material process in relation to simulation.

This dynamic between making and simulating is played out at every level of the exhibition. Unpainted false walls, of a type used in theatre production, imply that the exhibition itself is a type of model. Fiberboard panels entitled Drawing Boards have been machined using a computer controlled wood-router, and delicately finished by hand with graphite.

This layering of simulated and physical procedures is performed most elaborately in the paintings. Even the very act of painting is modeled – enacted at a micro scale on a platform in the artist’s studio. Fleeting material transformations – often on a scale invisible even to the artist – are captured using a macro lens on a digital camera. Later, these transitory moments are recreated in large pictorial-relief using a combination of digital 3D modeling, computer controlled machining, sculptural casting, and finally adhering a cast film of paint onto the surface of a canvas. While the production of the work is technologically mediated, the artist is keenly attentive to the vagaries of materials – allowing for chance occurrences in each stage of the process to function as generative elements of each individual work. The final result is a body of work that is simultaneously luminous and concrete, immediate and distant, uncannily simulated and corporeally present.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Prepared Ground at Taxter & Spengemann, 2011

The intimate monochrome paintings in Daniel Lefcourt’s exhibition Prepared Ground return to th subject of painting itself, yet here painting is never fully itself. On the one hand, the works are positivistic, presenting only brute materials and evidence of their manipulation. Impressions and textures function as proof of past operations, inviting us to reconstruct those operations in the present. Scraps of wood, water, cloth, paper, dirt, and other materials appear to have left indexical impressions on the surface of the painting. The works are not abstract, for as with artists who observe a strict adherence to procedure (Ryman, Barré) the concern is always to present the real – without illusion, and without editorializing.

Yet, in Lefcourt’s work the real manifests itself in unexpected, often counter-intuitive ways. In these paintings the traces, marks, and impressions, are not always what they seem. In fact, many of the impressions would be impossible to make with any direct technique. This is particularly true given the chosen materials’ propensity towards impermanence and chance. In Lefcourt’s work, gradual transformations – paper soaking into liquid, bubbles forming and dissolving, soil crumbling, dust blowing – have been frozen in mid-process.

To accomplish this task of freezing, Lefcourt devised an elaborate preservation method, in which digital photographs are translated into three-dimensions, and then output using a computer controlled router to carve low-relief molds. Acrylic paint is then poured into the mold, and finally peeled-up and adhered to the linen support. Here painting is understood not only as support an surface, but as particle and binder. Paint cast into Painting. In the final stage, the rote application of monochromatic oil paint both covers and discloses the topography of the surface.

The resulting traces of process – what might be called non-indexical traces – are at once simulated and substantial, shallow and fertile. Is this Painting behind itself?

Prepared Ground at Taxter & Spengemann, 2011

The intimate monochrome paintings in Daniel Lefcourt’s exhibition Prepared Ground return to th subject of painting itself, yet here painting is never fully itself. On the one hand, the works are positivistic, presenting only brute materials and evidence of their manipulation. Impressions and textures function as proof of past operations, inviting us to reconstruct those operations in the present. Scraps of wood, water, cloth, paper, dirt, and other materials appear to have left indexical impressions on the surface of the painting. The works are not abstract, for as with artists who observe a strict adherence to procedure (Ryman, Barré) the concern is always to present the real – without illusion, and without editorializing.

Yet, in Lefcourt’s work the real manifests itself in unexpected, often counter-intuitive ways. In these paintings the traces, marks, and impressions, are not always what they seem. In fact, many of the impressions would be impossible to make with any direct technique. This is particularly true given the chosen materials’ propensity towards impermanence and chance. In Lefcourt’s work, gradual transformations – paper soaking into liquid, bubbles forming and dissolving, soil crumbling, dust blowing – have been frozen in mid-process.

To accomplish this task of freezing, Lefcourt devised an elaborate preservation method, in which digital photographs are translated into three-dimensions, and then output using a computer controlled router to carve low-relief molds. Acrylic paint is then poured into the mold, and finally peeled-up and adhered to the linen support. Here painting is understood not only as support an surface, but as particle and binder. Paint cast into Painting. In the final stage, the rote application of monochromatic oil paint both covers and discloses the topography of the surface.

The resulting traces of process – what might be called non-indexical traces – are at once simulated and substantial, shallow and fertile. Is this Painting behind itself?